Subspecialty of ophthalmology and neurology

Neuro-ophthalmology is a subspecialty of ophthalmology and neurology that takes care of patients with diseases that affect the connections between the eye and the visual processing structures of the brain. Neuro-ophthalmologists treat a wide range of diseases that affect the optic nerves and brain including optic neuritis, ischemic optic neuropathy, brain tumors in the central nervous system affecting the optic nerves or the optic chiasm, strokes that cause visual loss or double vision, transient blindness, migraine with visual symptoms, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, mitochondrial disease, diplopia and strabismus, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, myopathies of the extraocular muscles, as well as diseases of the oculomotor cranial nerves resulting in ophthalmic movement disorders.

Neuro-ophthalmology is a critically important sub-specialty because neuro-ophthalmic diseases often result in permanent vision loss (i.e., Temporal arteritis, Fulminant idiopathic intracranial hypertension) and potentially death (i.e., cerebral Aneurysms, Acute Horner syndrome from dissection of the carotid artery, Pituitary apoplexy). Since neuro-ophthalmic diseases often involve a myriad of medical fields including neurology, ophthalmology, rheumatology, neurosurgery and internal medicine, it requires intensive training at specialized academic universities abroad that can teach how to diagnose and treat these complex disorders.

Neuro-ophthalmic diseases can be organized into two large categories based on the part of the visual system that is being involved: A) Afferent visual pathway disorders, B) Efferent visual pathway disorders.

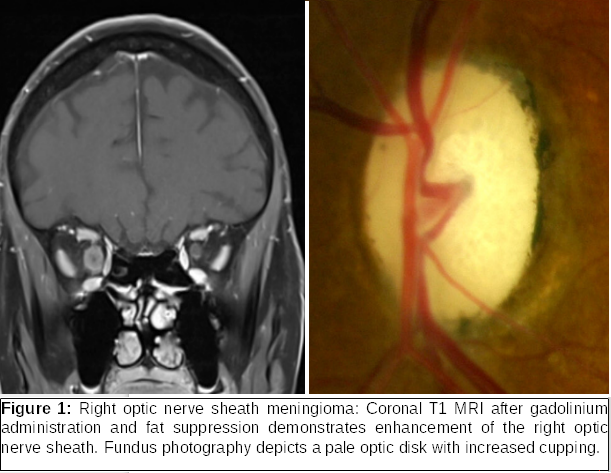

The afferent visual pathway carries visual information from the optic nerve to the vision processing center in the calcarine fissure of the occipital lobe through the optic chiasm, the optic tract, the lateral geniculate body and the optic radiation. Diseases that affect the afferent system include optic neuropathies (i.e., non-arteritic optic neuropathy, temporal arteritis, multiple sclerosis, NMO Spectrum Disease, Optic nerve glioma, Optic nerve sheath meningioma-Figure 1, Leber congenital optic neuropathy), Inflammatory and Infectious disorders, tumors in the area of the optic chiasm (i.e., Pituitary Adenoma, Craniopharyngioma, meningioma), and strokes.

The Efferent visual pathway is responsible for the coordinated movement of both eyes. and the size of the pupil. Many diseases may affect the efferent pathways including, nerve palsies (i.e., 3rd nerve palsy due to a posterior communicating artery aneurysm), Horner syndrome, myasthenia gravis, Thyroid eye disease, Dorsal Midbrain syndrome, multiple sclerosis, convergence spasm, Miller Fisher syndrome, skew deviation, and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy.

Efferent pathway manifestations can include anisocoria, internuclear ophthalmoplegia, nystagmus, external and internal ophthalmoplegia, gaze palsy, diplopia and strabismus.One role of a neuro-ophthalmologist is to differentiate routine ophthalmic cases from those that are potentially blinding and deadly. For example, cases with increased cupping of the optic disk (enlarged cup to disk ratio) can be incorrectly diagnosed as normal tension glaucoma when in fact they are due to a compressive optic neuropathy from a brain tumor. These cases are often misdiagnosed resulting in delay or failure of a diagnosis that can potentially be life-threatening. Another example is a patient being diagnosed with a 6th nerve palsy due to microvascular occlusion from cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension when in fact it is due to a compressive lesion in the cavernous sinus or along the course of the sixth nerve originating from the pons cause the palsy (i.e., schwannoma).

The major tool of a neuro-ophthalmologist in order to achieve a correct diagnosis is a thoughtful clinical examination. This fact in combination with the complicated nature of the cases results in a longer-lasting neuro-ophthalmic evaluation compared to a typical ophthalmic examination. After thorough examination, the neuro-ophthalmologist can request blood work or imaging in order to confirm or further investigate a case.

COMMON DISEASES OF NEURO-OPHTHALMIC INTEREST:

Optic neuritis is an inflammatory disorder of the optic nerve that results in demyelination and in a significant number of patients heralds the initial manifestation of multiple sclerosis (imaging with MRI is required to define the risk). This disorder presents with an acute, monocular, decrease in vision, distortions of colors and the visual field, with characteristic pain during eye movement. The majority of patients are women with a mean age of f 32 years. Recovery of vision usually begins between 2 to 4 weeks after the initiation of symptoms.

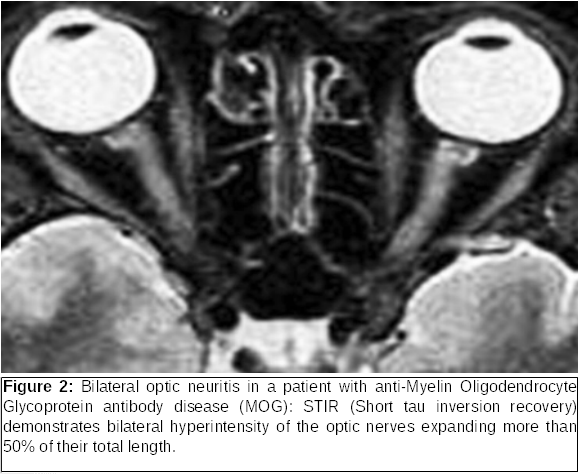

Based on the severity of manifestation and the imaging findings, the physician can treat the patient with intravenous corticosteroids followed by an oral taper (Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial). It is worth noting that the advances in the field of neuro-ophthalmology and immunology were a turning point and led to the identification of the Neuromyelitis Optica spectrum disorders-NMOSD, with major representatives being NMO and anti-Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein antibody disease (MOG). A remarkable number of cases which had been considered in the past and treated as “atypical optic neuritis”, such as cases with very decreased vision or bilateral involvement (Figure 2) turned out to belong to the NMOSD. This advance in immunology has led to a better understanding of clinical disease so that diagnoses can be made earlier and more accurately. It has also led to the development of specific and highly effective treatments to restore vision (steroids, plasmapheresis, immunoglobulins), as, otherwise, those diseases could lead rapidly to blindness, paraplegia or even death.

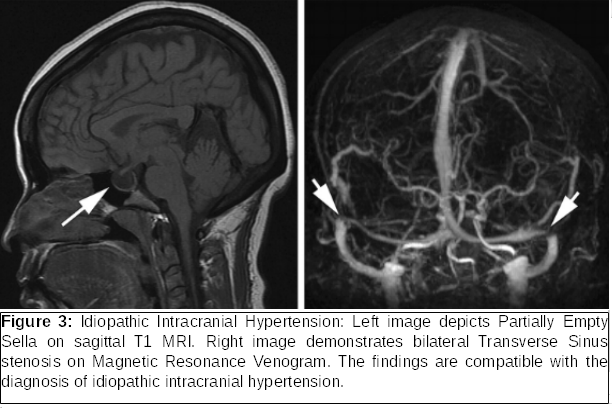

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension is a disease that affects women of child-bearing age in 90% of cases. Major risk factors include increased body weight and significant weight gain over a short period (>10% of the body weight). Common symptoms include headache, transient vision loss during rotation of the head or bending over, tinnitus or other intracranial noises, diplopia (due toa sixth nerve palsy, decreased vision and visual field deficits).

Diagnosis requires neuro-imaging (Figure 3) and lumbar puncture. Because IIH can lead to permanent vision loss and complete blindness, careful follow-up of patients is critically important in order to monitor visual function and adjust treatment (medication or surgical intervention [optic nerve sheath fenestration, shunting]).

Nystagmus is a rhythmic biphasic oscillation of the eyes. Pathologic nystagmus results from damage to either the vestibular system (central or peripheral) or to the visual pathway. Specific types of nystagmus can localize to a specific area, as in the case of Downbeat nystagmus (fast phase downward), which is often correlated with lesions and tumors in the cervicomedullary junction (i.e., Chiari malformation) as well as medications such as lithium.

Arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy is the ophthalmic manifestation of Temporal-Giant cell Arteritis and is a neuro-ophthalmic emergency. Sudden optic nerve infarction occurs because of inflammation that causes ischemia by narrowing vessel lumens secondary to vasculitis. The majority of the patients with GCA are over 70 years old and women are affected more frequently. Patients present with sudden, severe vision loss usually in one eye and then the other.

Visual symptoms are typically preceded by symptoms such as transient visual loss and diplopia are common. Many patients also have systemic systems symptoms including Rheumatic Polymyalgia manifestations (arthritis, pain on the shoulder), headache, jaw claudication during chewing or talking, fever, malaise, anorexia and weight loss. Unfortunately, even with prompt intervention the likelihood of vision improvement in the affected eye is very low.

Nevertheless, immediate therapeutic intervention (intravenous steroids) in highly suspicious cases of temporal arteritis is mandatory in order to decrease the likelihood that the fellow eye will become involved, as the possibility of second eye involvement is over 70% in a matter of days or weeks (unfortunately, even, under the appropriate treatment the second eye can go blind). Additionally, treatment is required for the protection of the patient’s life, as temporal arteritis can result in cardiovascular complications, such as aortic aneurysm, stroke and myocardial infarction. Diagnosis can be confirmed with temporal artery biopsy within 7 to 10 days after cortisone initiation.

Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) is the most common cause of acute painless vision loss in adults older than 50 years. The presumed etiology is insufficient blood flow in the posterior ciliary arteries leading to ischemia and infarction of the retrolaminar optic nerve. Patients with NAION are usually between 60-70 years and they present with sudden decrease in vision, the severity of which can range from mild to severe. Major risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, as well as nocturnal hypotension, an anatomically crowded disk (disk at risk), sleep apnea (new data question a direct correlation) and medications for erectile dysfunction (Viagra). 30% of patients will experience further deterioration of the vision, 30% will remain stable and one out of 3 will improve.

The risk of involvement of the second eye ranges in various studies from 15% to 30%. Interestingly, for reasons not clearly defined, the initial insult has a protective effect on the affected eye, as the likelihood of another event in the same eye in the future is very low. Modification of the risk factors seems to be the reasonable approach for the protection of the other eye for the time being, as cortisone use either to treat the affected eye or to protect the second one, has not been widely accepted in the clinical practice and is not supported by literature. Another approach favors the use of low-dose aspirin for the prevention of another event and for the cardiovascular protection of the patient in general.

Neuro-Ophthalmology Department

Director: Georgios Saitakis ΜD, MSc, PhDc, FEBO

Specialized Neuro-Ophthalmologist, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA

German

German Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά